The year is 2100. Latin America is sinking. Due to global warming the polar icecaps have almost melted completely. In addition the increased temperature has caused the global water mass to expand by almost 1%. As a consequence sea levels are rising at unprecedented levels globally. The coastline in South America is hard-hit by these events. From Patagonia in the south to Colombia in the north people are starting to leave coastal areas that have become uninhabitable. The Caribbean and the deltas of the Amazon and the Rio de la Plata become sources of climate refugees. The bulk of the refugees moves towards the major cities of the continent and settle in rapidly expanding informal settlements.

Paradoxically, Buenos Aires falls into both the category of an origin and a destination of climate refugees. As a major metropolis of South America, it becomes a natural destination for refugees from all over the continent, particularly from the Argentinian coast and the islands in Patagonia. However, its location at the mouth of the Rio de la Plata implies that the lower situated coastline itself is a major source of refugees.

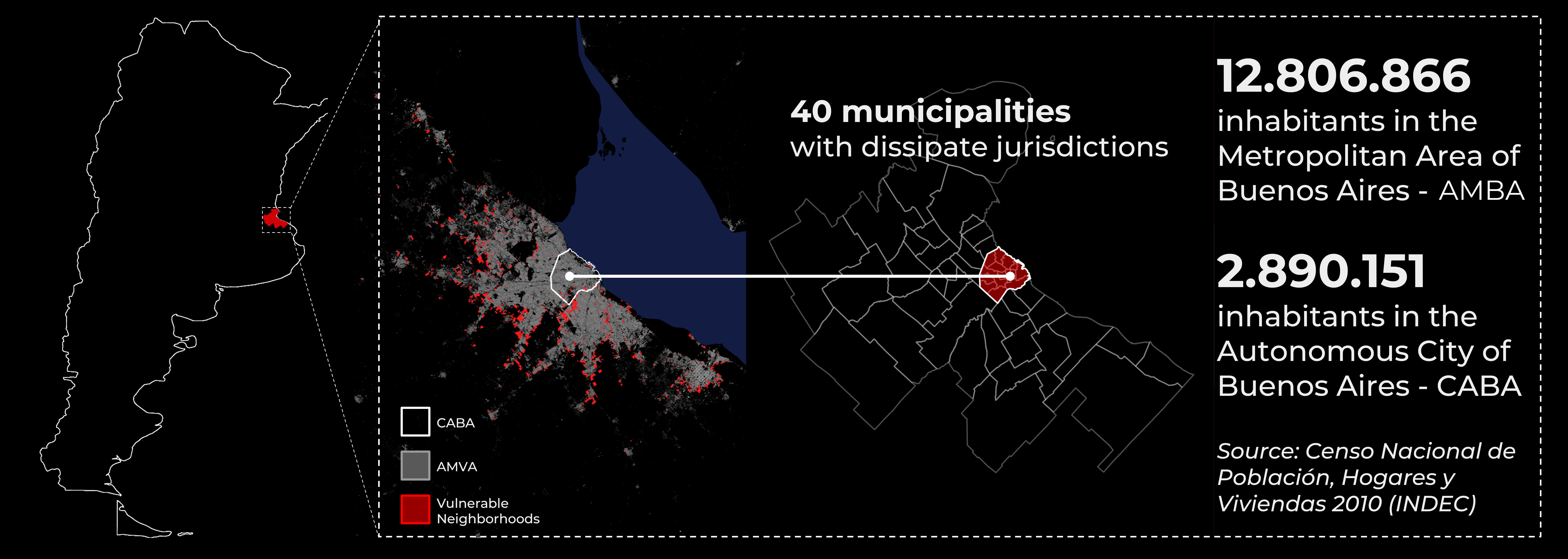

Buenos Aires, the capital of Argentina, is a city that highlights as a critical case study, due to the convergence of future migration inflows, as well as the risk of rising oceanic level. It is composed by the urban core of Ciudad de Buenos Aires, CABA, and its proximal conurbations of Area Metropolitana de Buenos Aires, AMBA, gathering close to 13 million inhabitants. It deals with a political obstacle, the CABA and the other metropolitan “partidos” have independent jurisdictions that do not intersect as one integral metropolitan administration. This materializes as an already existing barrier for developing joint strategies that involve the metropolitan municipalities as a whole.

In the scenario when the sea level rises, Buenos Aires, and especially its already densely populated urban core, will suffer from the convergence of three critical factors:

- The migrants coming from other cities of Argentina that will also be heavily affected by the effects of rising waters, moving to the already developed informal settlements in CABA’s peripheries.

- The wealthy communities from the northern part of the metropolitan area, which will be displaced from their current locations due to rising waters, and will be looking forward to finding a space in the urban center that has been saved from flooding.

- The vulnerable communities that are displaced by rising waters from their current locations concentrated in the south of the peripheries of the metropolitan area.

This three inflows of people will materialize as a desire for competing for one same space. This calls for the generation of a space for negotiation, fostered by the metropolitan administrations so they can stablish a democratic way of providing the necessary space for all the displaced communities.

Critical Shocks to Barrios and Land Use due to rising sea levels, increased migration and forced population displacement – As a direct impact of the rising sea waters, 21 barrios will experience damage to their critical infrastructure. This will create a cascade effect that will increase pressure on the critical infrastructure of the remaining barrios that will further be amplified by a sudden influx of immigrants and the sudden increase in population density. Taking this into consideration and corelating it with population growth trends, we estimate that the city of Buenos Aires will experience a sudden population increase due to mass migration followed by a population decrease connected to a higher mortality rate compared to natality rate. However, due to the rising sea levels and the decrease in dry land available, the population density will continue to grow even in times of population decline.

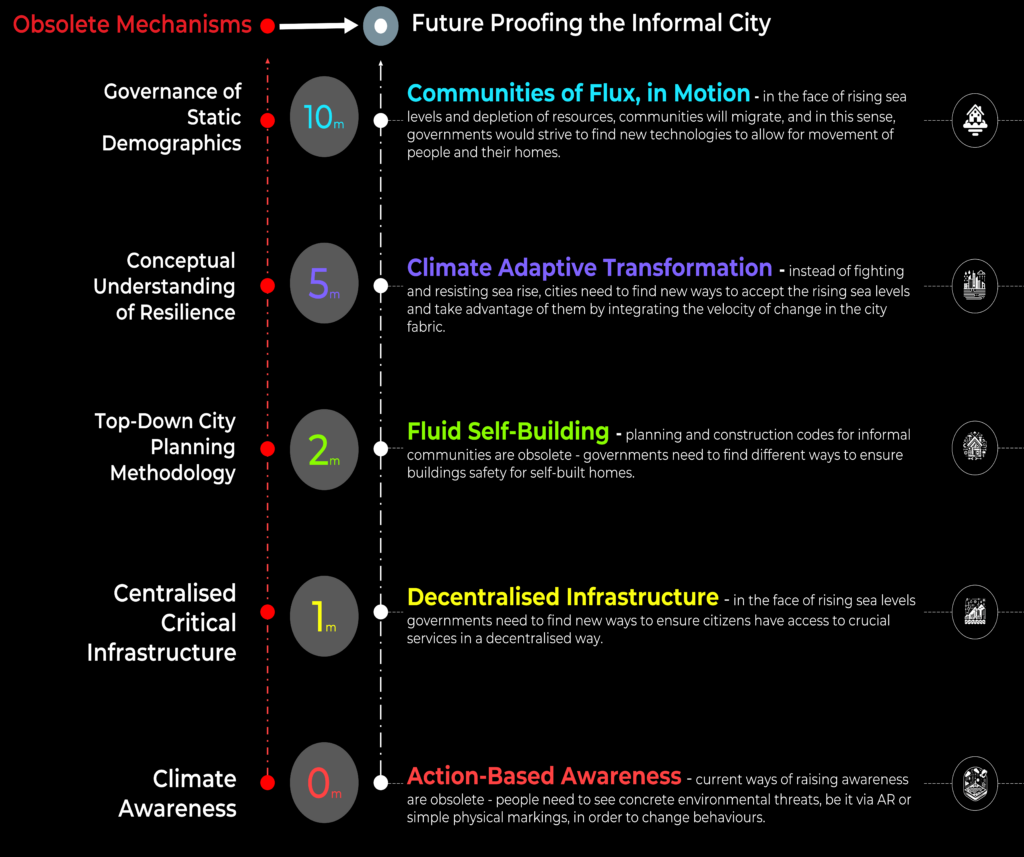

Having this scenario in mind we argue that classic mechanisms related to city planning and urban development need to be rethought and adapted to a possible new reality. We thus identified 5 different mechanisms that should be implemented depending on the sea level rise and also considered how these mechanisms should be rethought in the face of a new reality:

- Climate awareness – we argue that traditional ways of promoting climate awareness are absolute in the face of rising sea levels. In this sense a more critical and straight forward approach would be action based awareness. Some examples of action based awareness could be drawing a physical line in the city to shows exactly where the sea will rise to, or having a GIS platform where sea rise simulation is available to the public, or having AR (augmented reality) experiences in areas that will be affected so citizens can sea before hand how the physical place will change.

- Centralized critical infrastructure – we argue that having all critical infrastructure centralized does not offer a high degree of resilience, especially in the face a rising sea levels. A good example for this is the electrical infrastructure, which if damaged, can have a chain effect and leave a high number of citizens without electricity. The same can be argued with the water infrastructure and so on. With this in mind, we believe, that in the face of rising sea levels, a more decentralized critical infrastructure could offer a higher degree of resilience. A good example of this would be solar panels coupled with electrical storage capacity for individual households that would increase the degree of resilience.

- Top-down city planning – the traditional way of planning cities will not work in the face of rising sea levels and mass migration as it does not account for informal settlements. We argue that governments should accept that mass migration will lead to an increase in the number of informal settlements and figure out ways to ensure safety and structural integrity of the informal settlements. That could come in the form of guidelines for buildings (like Ikea assemble manuals for for buildings) that would allow for a more fluid self-building or targeted actions to increase the structural integrity of individual house holds. These actions could also be used as a census to study how prepared the informal settlements are to receive more migrants.

- Conceptual understanding of resilience – In response to the challenge posed by rising sea levels, we argue that cities must transcend traditional methods of resistance and instead embrace these changes. This involves integrating the dynamic nature of sea level rise into the urban fabric, finding innovative ways to adapt structures and city planning to accommodate water rather than defend against it. This climate adaptive transformation of cities could come in the form of newly build water canals on top of flooded infrastructure that interconnects communities directly contributing to their growth and prosperity via a a more efficient circular economy.

- Governance of static demographics – in the face of rising sea levels and depletion of resources, communities will migrate, and in this sense, governments should strive to find new technologies and policies that support the mobility of communities and their homes. This communities of flux approach anticipates the shift towards transient demographics, and would enable the smooth transition of populations and their habitats in response to environmental changes.